BLACK SABBATH’s Sabotage At 40 - “That Was Probably The Hardest Record, The Bleakest”

July 28, 2015, 9 years ago

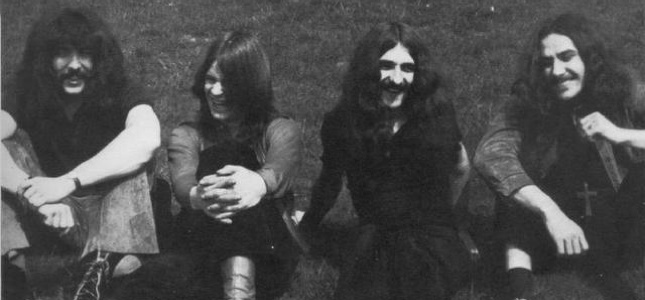

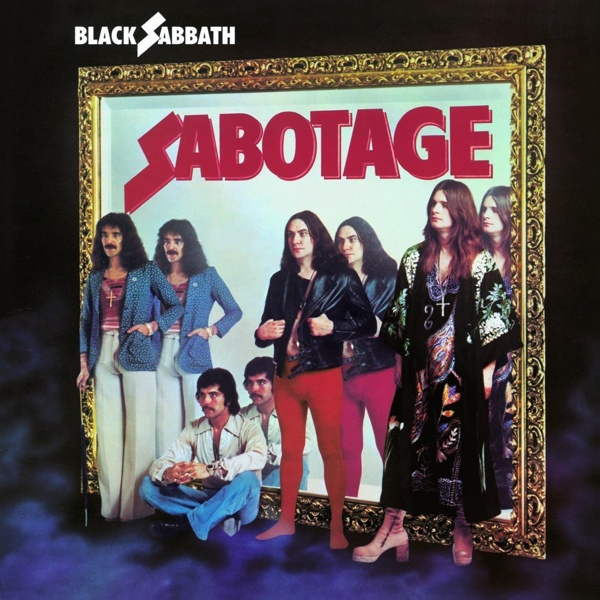

Today (July 28th) marks the 40th anniversary of what many dedicated students of the band consider the greatest Black Sabbath album of all time, Sabotage. The record would emerge from much strife the same year as Rainbow’s (unsure) debut as well as Led Zeppelin’s long-awaited double album Physical Graffiti. It is this writer’s opinion that Sabotage rivals the Zeppelin masterpiece as greatest album of all time (hard rock or otherwise), also to be perched above two landmark records from the following year, namely Judas Priest’s Sad Wings of Destiny and Rainbow’s second record, Rising.

In this abridged excerpt from my long out-of-print Black Sabbath book, Doom Let Loose, we celebrate the birthday of this sixth Sabbath slab—a record as progressive metal as it was doomy, as innovatively produced and arranged as it was headbanged—with a look at the way the band’s business affairs clouded the making of the record. As well, along that theme, we examine the two songs that had the most to do thematically with the band’s business shambles, namely “Megalomania” and “The Writ.”

From agony and strife would come a record that many of Sabbath’s maddest fans, this one included, consider the apex of the band’s career. Sabotage (Sabbath felt their career had been sabotaged by bad management) would combine the frantic, ecstatic creativity of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath with a returning heft, the band proving beyond a doubt through two cerebral records in a row that they fully deserved to swim with sharks like Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin in any waters, on any given day.

As it would turn out, the worst thing about putting together this poison-penned opus of a record was having to deal with the band’s collapsing business. Manager Patrick Meehan and the band were in a mammoth legal battle, and the paperwork was spilling into the studio, maddening for four working class lads cursed with a voracious, all-encompassing creative streak.

“That was probably the hardest record, the bleakest,” begins Geezer, “because we were in the studio and we were having lawyers come in. We were leaving the management at the time and he was suing us, we were suing him. He was trying to stop us from recording and freezing all our money. It was really bad times to go through. We used to turn up at the studio to go and write a song, and there would be like three lawyers waiting for us to put subpoenas on us, stuff like that. It took us about ten months to do the album because of all the interruptions we were having. But yes, the hardest would have been Sabotage but maybe also Never Say Die, and the most fun were the first three albums and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath.”

It can’t be stressed enough that even though Sabotage is seen by Sabbath fans the world over as a creative masterpiece (with a lesser portion calling it their best album), the band is still, 40 years later and to a man, so clouded by the tortuous assembly of it, that most gravitate to the similar Sabbath Bloody Sabbath as the creative pinnacle, Ozzy going so far as to call that album the band’s last.

“I think we changed, purely because of the system, the people surrounding us, the things we were involved with,” reflects Tony. “We started going through things we knew nothing about, the legal sides of things, all these hassles with management, stuff we really didn’t want to be involved with. But we were involved in it. And I think that really put a blunt end to what we were doing. Because suddenly here we are, musicians, or supposedly musicians, and then we needed to become businesspeople, which we weren’t. And try to work out, bloody ‘ell, what do we do now? Here we are having lawyer’s meetings, and turning up in court and all this sort of stuff, swearing affidavits, getting sued left, right and center. It was a part of our lives we had never seen before, and I think it really interfered with our music. I remember when we were doing the album, we were bloody getting writs in the studio, and then we were having to attend court because we were obviously going against Meehan. So it became very hard for us. We were seeing the other side of life we had never seen, so it was not a nice time, really. And I think changed us, to a point, because we were thinking more about how we were going to get out of this problem, than what we were supposed to be doing.”

At this point Bill, “the mother hen” of the band, took it upon himself to try deal with the monies. “Bill did, yeah,” laughs Tony. “We let Bill sort of start (laughs)... everybody had a part in the band, and Bill’s part was to sort out the money, go down to the bank, get the money, pay all the crew and pay each other and stuff like that, the general running of everything. But it went to his head (laughs). He started dressing up in suits and going down to the bank with his briefcase. It was another Bill! He really took it to another level (laughs), Bill. But it was funny. We had some bloody laughs over it. But everybody tried to do their part, and Bill worked hard and tried to do what he could. But of course Bill got, in them days, as time went on, more into the alcohol, and became an alcoholic, in the end. It’s very hard to talk to an alcoholic, even though he’s your best friend. When he’s drunk, it’s very difficult.”

“I think he was doing it simply because he was the only one who could be bothered at the time,” says Geezer. “I can’t really remember much about it. Yeah, he’d try and go get some money out of the bank for us, and phone up Warner Brothers and all that kind of thing.”

“Yes, I know that I spoke to a lot of lawyers,” confirms Bill on his new role. “I worked real close with Spock Wall. Spock took care of the stage and all of our equipment and our sound, even in the studio; he was like a major player. But there were still problems and lots of things going on and I just tried to fill in the holes really.”

Did you have an affinity for numbers?

“Well, no, Geezer is the smart guy in our band, as far as I’m concerned. He knows that kind of stuff. He’s real savvy with the numbers. No, I just had an instinct about... it was more like I was a mother hen than anything else. I still am. I still am. I’m like a mother hen when it comes to Sabbath; I really am. I’m just like that.”

“We spent a lot of time at it,” adds Graham Wright, beloved and indispensible road crew member. “I was driving Bill and Geezer down to London to what they call The Inns Of Court, to see the lawyers and barristers because they were in litigation. So there were quite a few weeks of that. They were trying to sort out their business problems. And that’s a stressful time for any band, particularly in those days. Because they had worked so hard. They got ripped off. It’s been well documented. Sure, they carried on, but I think there was a bitterness there towards management. It’s like anything: ‘Oh, why did we sign this and why did we go with this person?’ ‘It was your idea.’ ‘No, it was your idea.’ All that stuff comes into it. Meehan was a businessman. He was in it to get as much out of it as he could for himself. That breed of person, they’re ruthless. There’s no loyalty in business. Bands are made up of artists. I mean, it’s the same old story. Jim Simpson was sort of like a local promoter, from Birmingham. He was a nice guy. Once the band took off, especially in America, I think he was just out of his league. And then Patrick Meehan jumped in and said ‘Hey, come with me; I’m the big shot.’”

Graham’s partner in the rolling show, David Tangye explains the movement from Meehan and the imploding World Wide Artists, to a Mark Forster, who has since died. “I only ever met Patrick maybe once or twice. It was when I was working with Necromandus that I sort of met him. I wasn’t actually working for Black Sabbath. But he just seemed to be a manager, a London guy. It seemed that he had plenty of money and he was just sort of guiding them through. You just tipped your hat basically; you never really got involved when you’re in the road crew. You just go about your own business. Mark Forster was there when I was sort of doing it. Mark was sort of managing them, tour manager/tour accountant. Mark was a lovely fellow; he was a great guy for them. He was very, very well-respected in the music industry, and I think he did a lot for them in America, because he had a lot of contacts. He’d been around the block a few times. He was good for them in America.”

“At the time, after they’d finished with Patrick Meehan, which is like ‘74, it was like they were in freefall. They were just sort of gearing up to manage themselves. I think they talked about different managers and different people coming in and things like that, but there was no management at that time. When Mark Forster was actually brought in, they said we’ll manage ourselves, we’ll do our own sort of deal. Because they had all the court cases. Patrick Meehan came out with them about March of ‘76. They just took control again of themselves and Mark just sort of helped them along, basically, helped them in America. And of course they had big accountants in America looking after the business side. That was how it happened. The Patrick Meehan thing had rolled on a while. I don’t think they lost out a lot; I don’t really know. You couldn’t really put a comment on it because you don’t want to say anything that could be contentious. What I put in the book, those were the actual figures of what happened. That was out of the press. But they were quite happy to juggle all the management themselves and talk to the record companies themselves and do all that. And as I say, Mark did sterling working; he did great work.”

“All I know was that with Sabotage, it seemed the band were at their best, I think, because they were under pressure. And they were a bit pissed off at the way things were going for them management-wise. And as I say, if you read some of the lyrics, that’s the way it is, that’s what they are singing about. I just think they work best under those sorts of conditions. Because it all sounded demonic at the end of it, didn’t it?”

Side one of Sabotage on the original vinyl ends with the first of the record’s two business-themed tracks, a ten minute monster called “Megalomania,” which is this record’s “In My Time Of Dying,” no light comparison, given that Sabbath’s up-market rivals Led Zeppelin, four months before the launch of Sabotage, had issued Physical Graffiti. But yes, “Megalomania” is an evil epic of torrid, emotional movements. It opens like a schooner adrift and all dead or dying, slowly lifting off on a heavy Iommi riff somewhat similar in speed and structure to the Symptom one. As the song progresses different melodies unfold, and the record’s goodly production values reveal tricky little details of tone and tenacity.

“We were going through a very tricky time, with getting ripped off and stuff by tricky people,” says Bill, affirming that “Megalomania” and “The Writ” revolved lyrically around the band’s legal woes. Of course Geezer hides the detail well, and what emerges are songs where you can taste the torment, a torment powerful enough to spread to a sense of universality.

“They are intertwined actually both of those songs,” adds Bill. “’Megalomania’ was about greed or coveting; that’s at least what I interpret from the song. And then ‘The Writ’ is kind of like the coveter or the greedy person or whatever, the end result was ‘The Writ,’ if you like. They are kind of in the same family. I don’t know if there’s a big difference there. They are very different songs musically. Fantastic guitars, and I think the band sounded pretty hot on both of those songs. I liked Tony’s solo in ‘Megalomania,’ and I enjoyed very much putting a very straight beat to it. It was like one of the only times I got the opportunity to do a very straight beat for a number of bars (laughs). So that was kind of cool.”

“Like ‘Killing Yourself to Live,’ that was also written about management and record company people in general,” offers Geezer. “It was so long because we couldn’t figure out how to end the song. We just kept coming up with parts that were going to be new songs, but then we figured they would fit so we used them.”

Sabotage ends with a clang, our second featured song for this piece, “The Writ,” being one of the band’s under-heralded classics. The song revisits the sparseness and sluggishness of “Black Sabbath,” the guys bravely writing and executing a plod, nightmarish boiling cauldron sounds adding to the madness. As with “Megalomania,” it’s almost detrimental to the enjoyment of the track when one finds out the lyric is rooted in the band’s management troubles. But Ozzy delivers the song’s spitting venom with manic savagery.

“That was written about our management at the time and how we were just all fed up with everything,” affirms Geezer, “recording with a room full of lawyers. Ozzy came up with those lyrics and I thought they were really good. But it was just this whole situation with everybody suing everybody else. We just wanted out of it.”

As with “Black Sabbath,” or for that matter “War Pigs,” Sabbath pick it up later in the track, adding segues and secret passageways, again, as they’d learned through work on the preceding album, dovetailing in acoustic guitars with a sleight of hand that has the listener not watching the clock waiting for the next headbang. It’s a trip, a journey, and we’re all along for the developing, doomy story and lurching demise thereof.

“No, I loved that!” says Bill, on the challenge of playing this slowly and simply. “God, I enjoyed that; the less the better. Because you can really… for me, that’s what metal is about. Doing a slow song really loud, you just put the one down; you just put the bass drum where it has to go. You don’t need a lot. You can use the air and you can use dynamics and that is where the song is, you know? Sometimes just not even playing can bring out an incredible sound.”

Early copies of Sabotage included at the end of “The Writ,” a 23-second joke song, recorded at low level, called “Blow on a Jug.” Bill calls this one of his and Ozzy’s “family songs,” just something tossed off for light relief when in the mood. That’s Bill playing piano and Ozzy and Bill both singing, if you can call it that. “That was just an outro,” says David. “They used to muck about. It wasn’t intentional. Daft stuff. There was a lot of comedy with Black Sabbath. It wasn’t doom and gloom. It was more fun and games, down home. They didn’t live that part really. It was more of a laugh than anything else.”

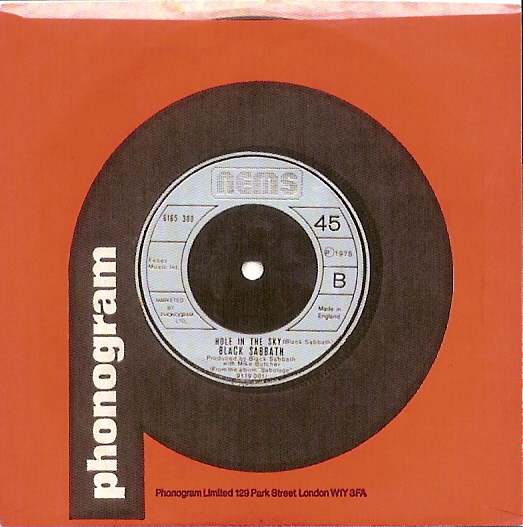

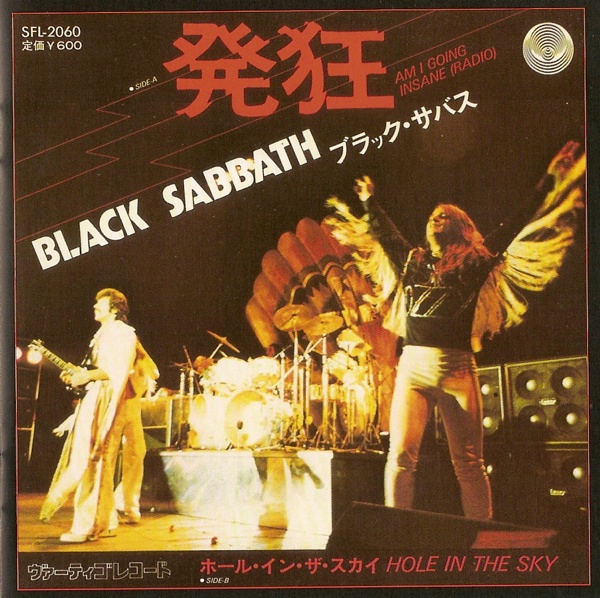

In conclusion, with respect to chart placement at the time, Sabotage saw further slippage for this band soon to be deemed out of steam. The record rose to #7 at home in the UK, where it stayed for seven weeks, but stumbled to a mere #28 in the US, eventually going gold for sales above 500,000 copies – it is the earliest Black Sabbath album not to have reached platinum status. No singles were issued until five months after release of the full-length when in February of ‘76, “Am I Going Insane (Radio)” came out, backed with “Hole in the Sky”—unsurprisingly, this weird, strangely irritating song failed to chart in either key territory.

Editor’s note: As mentioned, Martin Popoff’s Doom Let Loose: Black Sabbath, An Illustrated History is out of print, however signed copies of his Black Sabbath FAQ are still available from Martinpopoff.com.